My name is Chris Halaby and I have been a member of the KVR community since 2003. I have been using or helping to create music technology products since 1980. I helped to found Opcode and Muse Research, currently the home of KVR and not to be confused with Muse Research and Development, which is the home of the Receptor.

With this valuable space I will publish a series of articles and interviews with people that create products and with those that use them.

I have spent my entire adult life involved with music in one way or another. I started playing the guitar at the age of 12 and still play every day. I love any kind of music that has passion and energy.

Before I got my first real job I spent 8 years as a professional musician doing whatever I could to make a living, working at a music store, giving guitar lessons (I usually had about 25 students per week), playing casuals, working in theater orchestras, and the occasional recording session. Of course there were the many rock showcases for labels. In that day the only way one could get their music promoted and distributed effectively was to work with one of the record label cartels, so I spent lots of time going for the gold.

I thought the best way to introduce myself would be to write a short history of sequencing from my perspective, which will be separated into two parts: Dedicated hardware and software.

I have been sequencing music since 1980 when my friend Dan Newsom brought a Sequential Circuits Model 800 into the Music Annex recording studio where I was working. The Model 800 was one of Dave Smith's first products. MIDI had not been deployed yet so there was no real time recording, quantization, velocity editing etc. Given these limitations our particular use was to create arpeggios and ostinato patterns that were either too fast or too boring to play over an entire tune. Since the sequence could only be a series of equally spaced events the only way to get any kind of rhythmic pattern was to program spaces rather than notes in certain pulses.

We used a Roland TR-808 drum machine (also famous for the 80s clap sound and car shaking kick drum sounds in the 90s) to record clicks to tape - some as quarter notes and eighth notes and some with rhythm. It became available in 1980. We would then read the clicks with a product called the Dr Beat and that would clock the Model 800 in which the notes were sequenced.

The Model 800 would send these notes as gated control voltages (CVs) to Dan's specially retrofitted Mini Moog. You had to be very patient and if the power went out you had to start from scratch.

Sequential Circuits Model 800

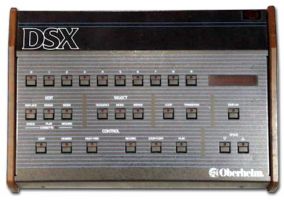

There was just no way that the Model 800 could be used reliably in a live situation so reproducing the music we had created was impossible. The answer for me appeared in the form of the Oberheim DSX. The DSX was Marcus Ryle's (founder of Line6) first product when he worked for Tom Oberheim. The DSX was the first sequencer that allowed the user to quantize note events, which was very important for a guitar player masquerading as a keyboard player. The DSX could hold up to 6000 notes and the really cool thing was that you could sequence patterns and string them together into songs. More on that later...

Oberheim DSX

It was designed to be part of a larger system that included their OB-Xa (and later OB-8) synthesizer and DMX drum machine so Oberheim added a parallel digital interface cable. The DSX connected to the DMX drum machine via a ¼" cable that contained the 96PPQ clock signal. The DSX also had other ¼" connectors in the back that allowed CVs and gates to be sent between to other devices that would accept that kind of signal.

I had become a fan of Oberheim products so I also bought an Oberheim Xpander, (which I still own) and that is what I used with the CV/Gate outputs of the DSX. Marcus was also involved in the development of the Xpander and, until his recent retirement, continued to make interconnected products for Line 6.

The only way to save a piece of work with the DSX was to use a cassette tape drive (very carefully!). Fortunately Jim Cooper, who worked for Tom Oberheim until he started his own business (JL Cooper) came up with a retrofit for the DSX that added a floppy drive (back when the media was actually floppy), making it much more useable at gigs.

Garfield Dr Click

I didn't completely buy into the system, opting instead for a Linn Drum, which was a blessing and a curse. The Linn Drum was designed by Roger Linn who many consider to be the father of the serious drum machine. The blessing was that the Linn Drum sounded incredible at the time (Wow! 8-bit samples!) and was extremely simple to operate. The problem was that the Linn Drum needed to see a 48 PPQ clock, while the Oberheim wanted a 96 PPQ clock. Subsequently the two units could not be synchronized without an additional device to resolve the different clocks. The Dr. Click (all this medical help...) from Garfield Electronics solved this problem and a variety of others. MIDI made the Dr Click obsolete, but Dan Garfield's one liners are still part of my personal NAMM lore, and our drummer was not out of work because you couldn't move all this stuff to gigs by yourself.

The Dr Click was a necessary part of any studio that wanted to use this stuff because none of the manufacturers could agree on what the clock should be among many other things. However with hard work by a number of individuals including Dave Smith MIDI was standardized in 1982.

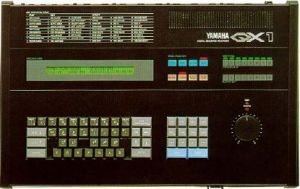

Yamaha QX-1

The DSX didn't have MIDI so I had a brief experience with one of Yamaha's first commercial attempts in the sequencing market, the QX-1. The QX-1 with had a clock resolution of 384 PPQ and lots of MIDI outputs, but it was really hard to use and not particularly flexible so I kept looking.

Roger Linn had me at hello with the Linn Drum so when his Linn 9000 first appeared I made a beeline to the nearest GC and grabbed one. It was a truly visionary product and the specs were a dream come true for the way I was working. It had a built in sequencer that sent MIDI. It both sent and received audio triggers so it could be used for drum replacement or enhancement. You could sample your own sounds into it and it came with a whopping 64K of RAM that could be expanded to an even more whopping 128K!. All the data including sequences and samples could be stored on the optional 3.5" floppy drive.

Linn 9000

Unfortunately the Linn 9000 also provided a lot of frustration. Although conceptually visionary, being a small company forced to compete with big players like Roland and Yamaha, the product was released before it was ready. Recording sessions with the 9000 could go completely awry as one had to figure what went wrong. In fact at one point there was talk of marketing a Styrofoam pillow that was shaped and painted like Linn 9000 so that you could hit it instead of your expensive piece of hardware. Also you were less likely to hurt your hand.

At the time there were very few project studios so I was able to eke out a living doing sessions with the 9000 and despite the problems it paid for itself.

Happily both Roger and Tom are friends and coincidently both are working on taking their respective original concepts into the next generation. Roger with his Linnstrument and Tom with his SEM.

My Linn 9000 lasted right up until Opcode developed our Vision Sequencer, but more on that later...

At the time I was playing in a techno band called Ariel Bond. We joked about how we could make as much sound as a larger group with just a few of us. Of course the joke was on us because just a few of us moved as much equipment as a larger group.

The Roland SH-101

I could write a book on what NOT to do when using sequencers in live situations. We had one song that required an opening sequence to be played by my Roland SH-101, which had a small sequencer built in. Unfortunately the SH-101 had no onboard memory so when we were headlining I would have to program the sequencing as the equipment was being moved onto the stage. It was either that or trust that nothing had gone wrong after the sound check. Forget that...! Most people just play with audio backing tracks these days.

Thanks for listening. Part 2 will be about the early days of software sequencing.

Chris.

Other Related News

Other Related News